On The Culture And Uniqueness of Action Sports

This week I'm reprinting a story I had published in Whitelines a couple of years ago.

Are action sports culturally ‘unique’ in the way they once were, especially as surfing, skating and snowboarding become ever more established Olympic sports? How do you reconcile the medals v. culture dichotomy that comes with this territory? Is it even possible to chase funding and medals while also safeguarding the grassroots culture that signifies a healthy scene? Are the people involved in making these decisions even aware of this debate, and does it factor into their decision-making? And why does any of this matter, anyway?

These are perennial themes on my podcast, and they’ve come up again in recent weeks following the appointment of GB Snowsports head Vicky Gosling as chair of British Surfing.

I began to write a blog about it: until I remembered that I’d already written an entire essay on this topic for a recent edition of the Whitelines annual. So, with the kind permission of the team at Whitelines, I’ve decided to reprint the entire thing in this week’s newsletter, which is out this Monday.

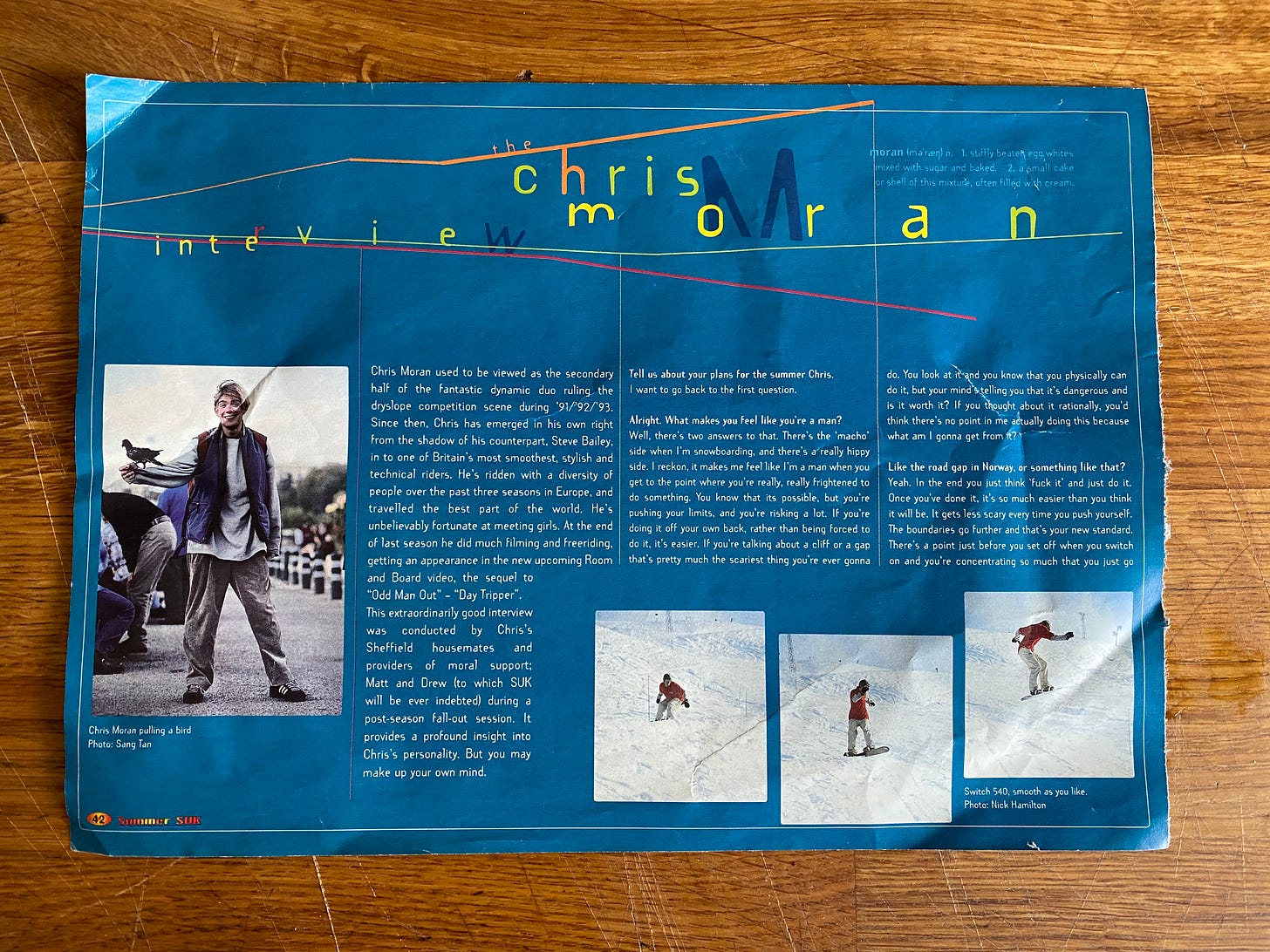

The first time I interviewed a professional snowboarder was in July 1995. I can be that specific because I’ve just dug the actual issue out of the loft. I was 19, and it was eventually published in the 1996 Snowboard UK summer special.

The subject was none other than Chris Moran, ex-editor of Whitelines and at the time one of the UK’s most respected and certainly most stylish professional snowboarders. He’s also one of my oldest and closest friends, which is how I ended up writing the interview in the first place.

It was a more innocent time - and not just because we recorded the interview two days after we got back from watching Oasis headline at Glastonbury at the height of Britpop mania, and the main sequence was a cab 5 off a cat track.

In the intervening 24 years, I’ve interviewed hundreds of snowboarders, skateboarders, surfers; either during my years working for Whitelines, as a freelance journalist; or, latterly, for Looking Sideways, the podcast I started in February 2017.

I’ve chatted to Tom Burt about filming A View to A Kill, and interviewed surf legend Herbie Fletcher at his studio. I’ve listened in reverent awe as a delighted Alex Honnold talked me through his free solo up El Capitan, and had skater Jamie Thomas invite me to his home to talk me through his mid-life crisis.

The last snowboarders I interviewed were Lesley McKenna, Hannah Bailey and Lauren MacCallum while I was up in Aviemore in April 2022. Listening back to this one, it’s striking how little has changed since I talked to Chris Moran way back in 1995.

Community. Progression. Culture. Competition. These themes were covered in my first interview with Chris and my last one with Lesley, Lauren and Hannah – 27 years later. And they have been the consistent themes in the hundreds of interviews I’ve conducted about snowboarding, skateboarding, surfing – even climbing - ever since.

Yet while the sentiments expressed by Chris, Lesley, Hannah and Lauren might not have changed in over two decades, everything else about action sports sure has.

Because in case you hadn’t noticed, action sports are massive in a way nobody could have imagined all those years ago. Surfing and skateboarding are in the Olympics. British snowboarders - unthinkably - have won Olympic medals. Adidas and Nike are two of the world’s biggest skate brands. And so on.

And lately, I’ve been wondering - are action sports still ‘special’ in the face of this incredible change?

I decided to look at the themes that have come up time and again in the 27 years I’ve been involved in this whole daft game - community, culture, progression, competition - in an effort to find out.

How have they changed? And what does it tell us about the ‘soul’ of action sports, if it ever really existed in the first place?

Community

Community has always been at the heart of the appeal of action sports and has probably been the most consistent theme among everybody I’ve ever interviewed.

Take BMXer Bas Keep, who told me that discovering the ramp near his house, and the other kids riding it, changed his life forever: “I just remember being so in love with it. It was a magical feeling. It felt like the world existed and then there was this secret that only we knew about”

When I chatted to Jamie Thomas, he described his own discovery of skateboarding in the same terms. “I always had this sense of not belonging. And then you find skateboarding and what comes with it is a whole group of people who don’t belong, and you all don’t belong together to something that is amazing. It’s so cool in that way, and that’s what makes it truly unique”.

The importance of community in action sports is undoubtedly real - and powerful when it is harnessed for good. Look at the Long Live South Bank campaign, which succeeded because it positioned the vibrant local skate community as a crucial cultural counterpoint to an increasingly homogenised city landscape, as spokesperson Stu McClure explained when I interviewed him in March 2018.

Or Moy Hill Community Farm, established in County Mayo on the west coast of Ireland by a community of surfers who after years chasing waves across the globe decided to dedicate their lives to a higher purpose in the hope of inspiring others, as co-founder Fergal Smith explained to me when we chatted in September 2017.

And yet, as have also discovered with depressing regularity, sometimes this much-vaunted sense of community has been found sadly lacking when it matters most. Particularly for women, as various guests have explained to me.

Among Looking Sideways interviewees, the most infamous example of somebody cast out from the community is Cori Schumacher, surfing’s first openly gay world champion. Cori is an avowedly political thinker who was attacked and driven out of the industry for having the temerity to suggest that the way the ‘Big Surf’ industry sexualised women was toxic and unhealthy.

The vitriol Cori received for daring to point this out (“Quick someone shoot that Cori feminist dyke” reads one typical comment), and the fact that she eventually felt it necessary to quit professional surfing “to save her relationship with surfing”, as she put it, doesn’t exactly scream of a happy, inclusive community. As she put it herself, “I’m an inconvenient champion. I’m inconvenient for the dominant status quo”.

Snowboarder and agent Circe Wallace is another figure who has found the support of the community lacking, particular in skateboarding, where she has forged a career as an agent managing skaters such as Paul Rodriguez and DeShawn Jordan.

Circe has enjoyed amazing success as an agent, but during our conversation made it clear it had come at a personal cost and described herself as a “pariah” among the predominantly male skateboarding industry. Circe’s experience, she explained, was that there is opportunity for women but they face more barriers than their male counterparts: “You have to demand it. You can sit around all day being the victim of your own circumstances, or you find ways around it”.

Culture

It’s a cultural argument, obviously. All communities come with cultural codes. And the pull of action sports culture is particularly strong.

From Olympic medal-winning snowboarder Jenny Jones (who told me that “the experiences and adventures that come with snowboarding” were her favourite thing about it), to skateboarder Pete Hellicar who enthused about skateboarding “expanding the boundaries and making the world seem larger”, almost everybody person I’ve ever interviewed has cited the culture that comes with each action sport as being easily as important as the actual act of riding a board.

Anybody remotely interested in action sports culture will recognise this chat. It’s a big part of the initial appeal of sideways culture when anybody gets into it. It’s the idea that these different elements add up to an ‘otherness’ that make board sports culturally, well, different. We’re not like football, rugby, athletics or tennis. Time and again during my Looking Sideways interviews, this idea comes up as the thing that really got people hooked in the first place.

Early on in the Whitelines years we realised this was ripe territory for piss-taking, and spent an unhealthy amount of time ridiculing the entire notion: middle-class white kids taking expensive holidays and then harping on about ‘keeping it real’; companies publicly peddling that same message in ads while ruthlessly cutting their team riders when they reach the age of 24, as happened to Michi Albin when he was dropped by Burton at the height of his career.

Dickish though it undoubtedly was, we were attempting to make a serious point. That this uneasy balance - a pseudo-profound reverence for what is ultimately tooling around on useless wooden toys; while simultaneously understanding that there CAN be something deeper at play - has always been the fairly glaring contradiction at the heart of action sports.

And as action sports place in society has evolved, that contradiction has become ever more pronounced, which has been another prevalent theme over the years.

Take surfing, which pretty much invented the narrative that first skateboarding and then snowboarding adopted. It’s probably the easiest example of how a counter-culture that likes to see itself as far removed from the mainstream can very quickly become extremely conservative, as surf journalist and film-maker Jamie Brisick pointed out when I met him in Malibu in March 2019: “The reason I’m so disappointed in how conservative surfing is? Because I expected so much more from surfing”.

It’s one example of the way that these codes can become quickly shackles with which to judge and even inhibit the very self-expression that is supposed to be at the heart of our culture.

The idea of ‘core’ is another. All board sports have their own version of this, and it’s pretty obvious where it came from – as an attempt to safeguard that uniqueness that was supposed to be the point in the first place. The problem with that, as a disturbing number of guests have related, is it promotes the idea that there’s a ‘right’ way of doing things, and that eventually leads to a debilitating snobbery. All of which leads us nicely to ….

Progression

Or creativity, if you like. Another key component of the appeal of action sports, and something cited by absolutely everybody I’ve interviewed over the years.

“Skateboarding was a creative outlet for me in order to not be told what to do”, explained Jamie Thomas. “Skateboarding fed that ability to be creative and be independent. And do things your own way. You can make it your own. I really loved that and thrived on that”.

The great thing about this is that it’s something everybody can recognise, no matter what their level of skill or experience. For me personally, one of the great joys of getting older is understanding how my relationship to action sports progression has simultaneously widened AND narrowed as the years have passed.

Through my teens and twenties, progression meant learning new tricks. Freestyle, basically. In my 40s, progression has been boiled down to the quest to do one nice turn on a surfboard. And I’m enjoying the whole thing more than ever.

My experience isn’t unique. The fact that everybody has their own relationship to progression is why the whole thing is so fun in the first place, and has been referenced by pretty much everybody I’ve spoken to over the years.

And it’s why these notions of ‘coreness’ and the ‘right’ way of progressing, which our culture can so easily lend itself to, can be so pernicious.

It’s something no less a figure than Billy Morgan alluded to when I interviewed him in January 2018 ahead of the Pyeongchang Olympics, and asked him to address the widespread ‘he’s a glorified gymnast’ sniping that accompanied his rise to prominence.

“I feel like they’ve almost ruined the coolness of it by being too cool”, he explained. “And being worried about being too cool. If you think back to the origins of boardsports it was about being a rebel renegade and doing whatever you want. Now it’s like ‘No, this is how you be cool. You need to do these things’. And that’s not how I feel it should work. The fact that there’s no ‘right’ way of doing it is supposed to be the point.

In certain cases, this attitude can actively inhibit progression, as demonstrated by an ongoing debate in the arena of big wave surfing I’ve been covering over various podcast episodes.

It is centred around Paige Alms, Keala Kennelly, Bianca Valenti and Andrea Moller, a group of - well - progressive women who have pushed their limits and redefined how women can perform in waves such as Jaws and Mavericks.

It’s the kind of bravura push that you’d think would be universally celebrated for summing up that questing spirit of progression that is supposed to lie at the heart of action sports culture. Except not everybody has been happy about it, meaning that the entire episode has become as much about campaigning for gender equity as about progression in big wave surfing.

Photographer Sachi Cunningham, who has documented much of this scene, gave me her take when I interviewed her in San Francisco in March 2019.

For Sachi, the arguments male surfers have been making about such waves being “too dangerous for women” is about more men being threatened by women encroaching on one of the last remaining bastions of maleness than it is about female safety.

“I think there’s something about the great outdoors that men seem to still have ownership over, and are threatened by female presence. It’s like this last frontier where men can be men, and its men only. I don’t just think that applies to big wave surfing, I think it applies to mountaineering and other outdoor sports as well. I think there’s something about wilderness that men are more protective over. When a woman steps in, they feel it lessens what they do”.

For Sachi, the repercussions are obvious – it holds women back and inhibits progression.

The reactions to two recent notorious big wave incidents - Greg Long at Cortes Bank in 2012, and Maya Gabeira at Nazare in 2013 – prove the point.

Long’s tale of suffering a three-wave hold down that almost killed him was rightly lauded (not least by me during our April 2019 interview in Huntington Beach) as a classic redemption tale - and has only added to his reputation.

Gabeira, in contrast, was pilloried as irresponsible by no less a figure than Laird Hamilton. As Ken Bradshaw pointed out at the time, the history of big wave surfing is full of examples of men who have died or almost been killed – “…yet nobody is saying they shouldn’t be surfing those waves”.

It’s a double standard that was summed up nicely in a blogpost at the time: “So Eddie would go - but Maya should think twice?”

The situation at Mavericks eventually changed when the women formed a pressure group called the Committee for Equity In Women’s Surfing and successfully lobbied the California Coastal Commission to support the addition of a women’s heat to Mavericks as well as guaranteeing equal pay.

Which, when you think about it, is a pretty damning indictment on the lengths women have found it necessary to resort to achieve the same levels of cultural and progressive parity that are supposedly such an enshrined feature of our world.

There’s another layer to this, too. Which is that the one area that is actually driving the biggest change in action sports culture is … competition. You know, that murky grey area where action sports and traditional sporting cultures meet, and which thanks to the Olympics has been the biggest ‘soul of action sports’ battleground for at least two decades. Let’s look at how.

Competition

Before we start, let’s put one trope to bed once and for all – that action sports are the antithesis of traditional competition. That’s always been clearly nonsense - look at riders like Craig Kelly, skaters like Gonz or surfers like Shaun Tomson. Fearsome competitors, one and all.

The truth is that the competitive urge has always been a key part of the action sports ecosystem – it is just understood and appreciated in a radically different way than it is in mainstream sports.

As these two plates have collided, interesting and unexpected things have happened to the culture – both positive and negative.

The Olympics is the obvious example. For years, as we all know, action sports culture has defined itself as being the antithesis of everything the Olympics stand for.

But as uncomfortable as it might be to admit, it is undeniable that for a new generation, the wider cultural influence of the Olympics is having a positive influence on their place in the community.

It’s a result, according to Cori Schumacher, of the Olympic platform, “forcing none-traditional sports to engage with Olympic values and reckon with their sexism, racism and homophobia. The drive towards the Olympics has opened surfing, skateboarding and snowboarding up to equality and will change some of the institutional things those cultures have been able to get away with”.

Yet in other ways the Olympics still – after all these years! - symbolises the mainstream’s inability to comprehend our unique approach to competition and sums up the reality of the huge changes that have been wrought on our culture as a result.

Snowboarder and Olympian Kelly Clark summed it up best when I interviewed her at her Folsom home in March 2019. Clark is the most successful competitive snowboarder of all time - 200 events, 137 podiums, 78 winds, 6 X Games medals, 8 US Open half pipe titles, two bronze and one gold medals won over the course of five Olympic Games. If any athlete has had a career reminiscent of a ‘traditional’ sporting athlete, it is Kelly Clark.

For Kelly, the difference between competitive snowboarding and other competitive sports is obvious. “Sports like athletics are about execution. Snowboarding, surfing and skateboarding are about progression. That’s the difference”.

Back in the mid-90s, the mainstream inability to understand this distinction was why snowboarders fought so hard against FIS taking control of their pathway into the Olympics, and is why surfers and skaters are nervous as their sports take their own fledgling Olympic steps.

And well they might be. Because the truth is that the mainstream still doesn’t get it – and as that influence grows, our culture will change in irrevocable ways, from grassroots to professional level.

The Future

I remember really clearly where I got the idea for this article. It was April 2018, and I’d just got out of a meeting at the BOA headquarters in London. In attendance were representatives from GB Snowsport, UK Sport and GB Park and Pipe, the body that had masterminded Team GB’s skiing and snowboarding success at the 2018 Olympics.

I was there because I’d helped GB Park & Pipe Programme Manager Lesley McKenna come up with a communication and coaching strategy we’d used in the lead up to the Pyeongchang Games.

The idea was based around safeguarding the ‘specialness’ of action sports I referred to at the start, and went right to the heart of Kelly Clark’s point – that fundamentally action sports athletes need different treatment from their traditional sporting peers if they are to succeed in a mainstream sporting arena like the Olympics.

We’d coined our approach ‘Radical Gains’, thinking that this nod to the old marginal gains cliché would help people less versed in action sports culture get their heads around it, and in the lead up to the meeting we were feeling pretty pleased with ourselves.

After all, snowboarder Billy Morgan and skier Izzy Atkin had won medals - an incredible return for a nation like Great Britain. And a new generation of riders had gained valuable experience at their first Games. The entire Radical Gains approach appeared to have been vindicated.

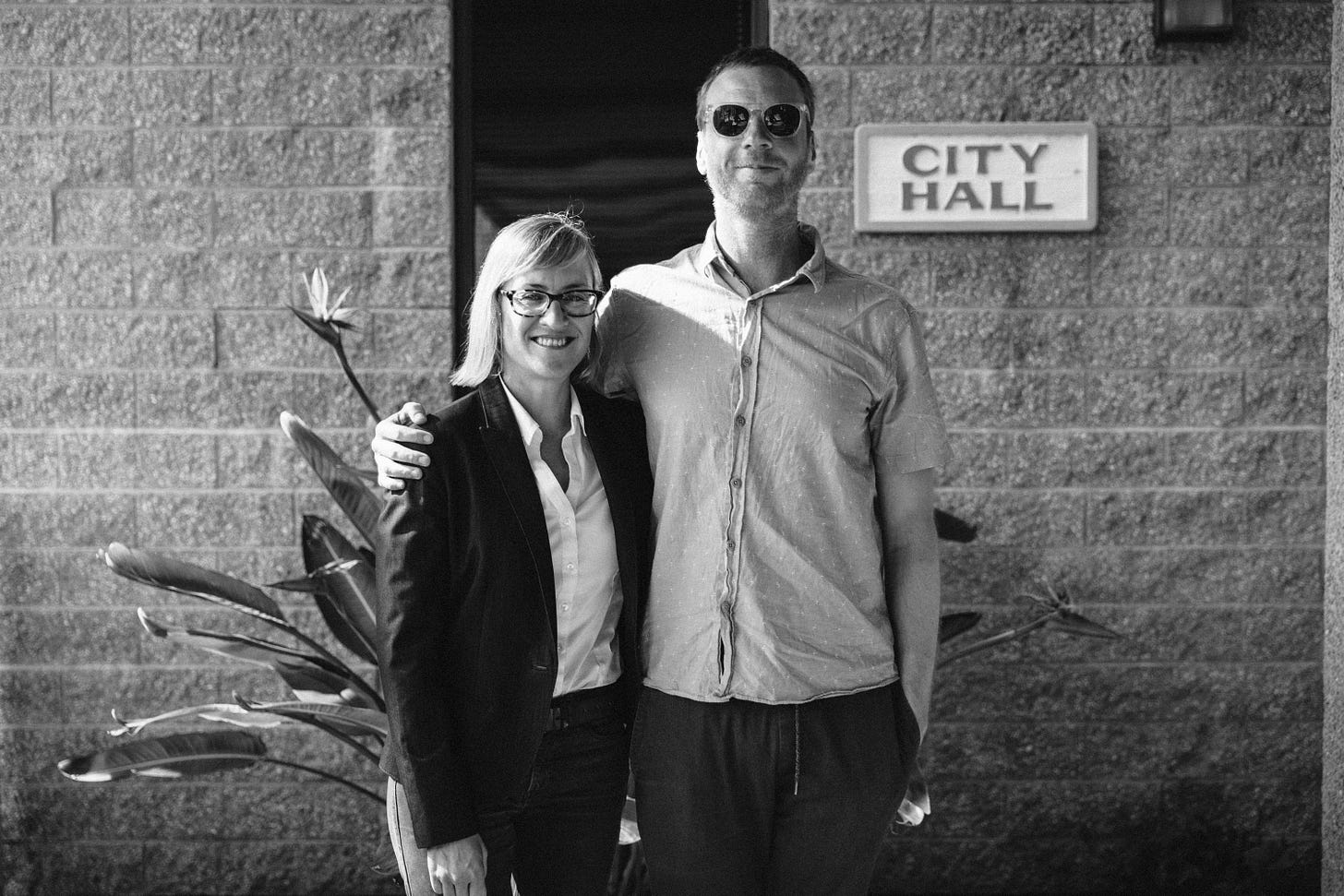

The meeting that day was chaired by Vicky Gosling, the new GB Snowsport CEO. Gosling was a sporting administration apparatchik with extensive experience in the traditional sporting world but zero working knowledge or even, it soon became apparent, any curiosity whatsoever about action sports culture.

It didn’t take long to realise that Gosling had a pretty different take on things. And she really wasn’t buying this whole ‘action sports are special’ argument.

“You’re not telling me that snowboarders care that snowboarding is in the Olympics?” she asked me at one point. “For them, it’s just another sport”.

Later, in the pub, I pondered the implications of the conversation. Obviously, it went against everything I believe in, and the views of people like Kelly.

But I couldn’t help but wonder: what if the whole idea of the ‘specialness’ of action sports is only being kept alive by people like me, who are beholden to an idea that is well past its sell by date?

So what do I think now, after mulling it over for the best part of four years? I think the truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle. Because the action sports community is just like any community. As we’ve seen, it has flaws worth overhauling and some truly horrible, toxic elements that need eradicating.

Like any western society, there is clearly an invisible, invidious patriarchy at work. Most men don’t notice it, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t real, as every woman I’ve interviewed has eloquently testified. And the effect of this is undeniably damaging.

But it also has unique principles that are worth protecting. Foremost of these, as Kelly Clark pointed out, is progression, which was always supposed to be the point and which, clearly, is now more important than ever.

It is progression that has always been at the heart of action sports’ uniqueness. Forward movement and flux are supposed to be the point.

I’m not just talking about individual progression either, which is what tends to come to mind when we think about the concept. It’s not just about adding an extra 180 or cork. Cultural and societal progression are equally important.

In that light, progression is about pushing our sport in new and creative directions; becoming more aware of our relationship to the environment, and more inclusive as a community of board riders. Not trying to freeze the culture in aspic by vehicles such as localism, or trying to use mechanisms such as the Olympics to turn it into any other sport, and hence lose what made it culturally unique and attractive in the first place.

The more that action sports infiltrate the mainstream - hell, become the mainstream - the more we need to nurture and protect this principle into the future. Only then can we continue to fulfil the potential that got us all into this whole game in the first place.

Because that’s the true uniqueness of action sports. And that’s the culture that sets it apart, and which is worth standing up for.