Insights: Five Thoughts on I Am Dynamite!

Or what I learned from a brilliant biography of Nietzsche, my favourite book of the year so far.

It’s only April, but I think I might already have a contender for my book of the year: I Am Dynamite!, Sue Prideaux’s fantastically-entertaining biography of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

I stumbled across it via the always-excellent Five Books newsletter, which made a passing reference to the Nietzsche book in a glowing review of Prideaux’s more recent biography of Paul Gauguin.

It seemed like a good way to find out more about Nietzsche, somebody whose name is dropped frequently, but who I know next to nothing about.

But, more importantly, the tone of the review (another reason Five Books is one of my favourites) made me know I’d love Sue Prideaux’s writing.

And so it proved. Dry, cerebral, stylish, witty: Prideaux is clearly drawn to flawed historical egotists, and she has a lot of fun with a cast of brilliantly odd and entertaining characters. And, of course, she also does a great job of explaining why Nietzsche holds such an important place in the history of Western philosophy.

Still, by far the most interesting and entertaining aspect of I Am Dynamite! is the way Prideaux explores the tangled, narcissistic creative insecurities of Nietzsche and collaborators such as his one-time friend-turned-nemesis Richard Wagner.

It’s all there. The fragile egos. The deep need for validation. The wild mood swings between ‘Actually, this is pretty good!’ to ’Christ. This is shit’.

In other words: exactly the kind of neurotic energy I see in myself every time I sit down at ye olde laptop, or go to share my work in Insta.

Anyway, I enjoyed this book so much I ended up taking notes; which eventually evolved into this short piece.

Sure, there are a few reflections on the book itself, and a few thoughts on how Nietzsche’s views have a certain diabolical resonance today.

But mostly, it’s a reminder that the creative meltdown has a long and noble tradition - and that even history’s tortured geniuses were just trying to figure it out, like the rest of us.

1. Nietzsche was an early Blue Health adopter

“Never trust a thought that occurs to you indoors” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo

Nietzsche, Prideaux tells us, “did his best thinking in the open air. Place was vitally important to him.”

Swimming was a key passion, a “lifelong recreational delight.” A proto-cold dipper who, in another era, would deffo have worn his camo Dryrobe on the weekly Lidl run, I Am Dynamite! is full of references to what these days must by law be referred to as ‘wild swimming’.

At times of high stress, in a manner familiar to anybody who has looked at social media at any point in the last decade, it also endowed considerable mental health benefits - as in Bayreuth in 1872, when, overwrought by his falling-out with Richard and Cosima Wagner, he sought sanctuary in the garden of his friend Malwida von Meysenbug:

“He took long swims in the waters of the little river that flowed through the garden. It was a regime that did him so much good that … he had to admit that his soul could not help but submit.”

Equally vital to his wellbeing were his legendary rambles around the Alps. In the early years, intense, transformative conversations during epic Alpine walks with figures like Richard Wagner or Lou Salome helped shape his thinking.

Later, as he matured as a philosopher, these increasingly transcendental yomps were more solitary, but no less creatively essential.

With his eyesight failing, works like Thus Spoke Zarathustra were, Prideaux tells us, composed on the move, and:

“..divided into the small, intensely compressed sections that he could manage to organise while on his four- or six-hour walks and transfer into his notebooks without any practical help. The landscape of his inspiration took the path round the two little lakes of Silvaplana and Silsersee whose intensely turquoise water formed the shimmering floor to the luminous overhang of steep-sided mountains capped with eternal snows. It was a completely self-contained world…”

Little wonder that, towards the end of his life, a reflective Nietzsche concluded the following:

“Philosophy, as I have understood and lived it, is voluntary living in ice and high mountains.”

2. You can’t escape history

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” – Mark Twain

Like all philosophers, Nietzsche was thinking on the grandest scale of all, trying to understand the movements of history, the nature of creativity, and recurring patterns of human behaviour within the context of four thousand years of cultural thought and historical suffering.

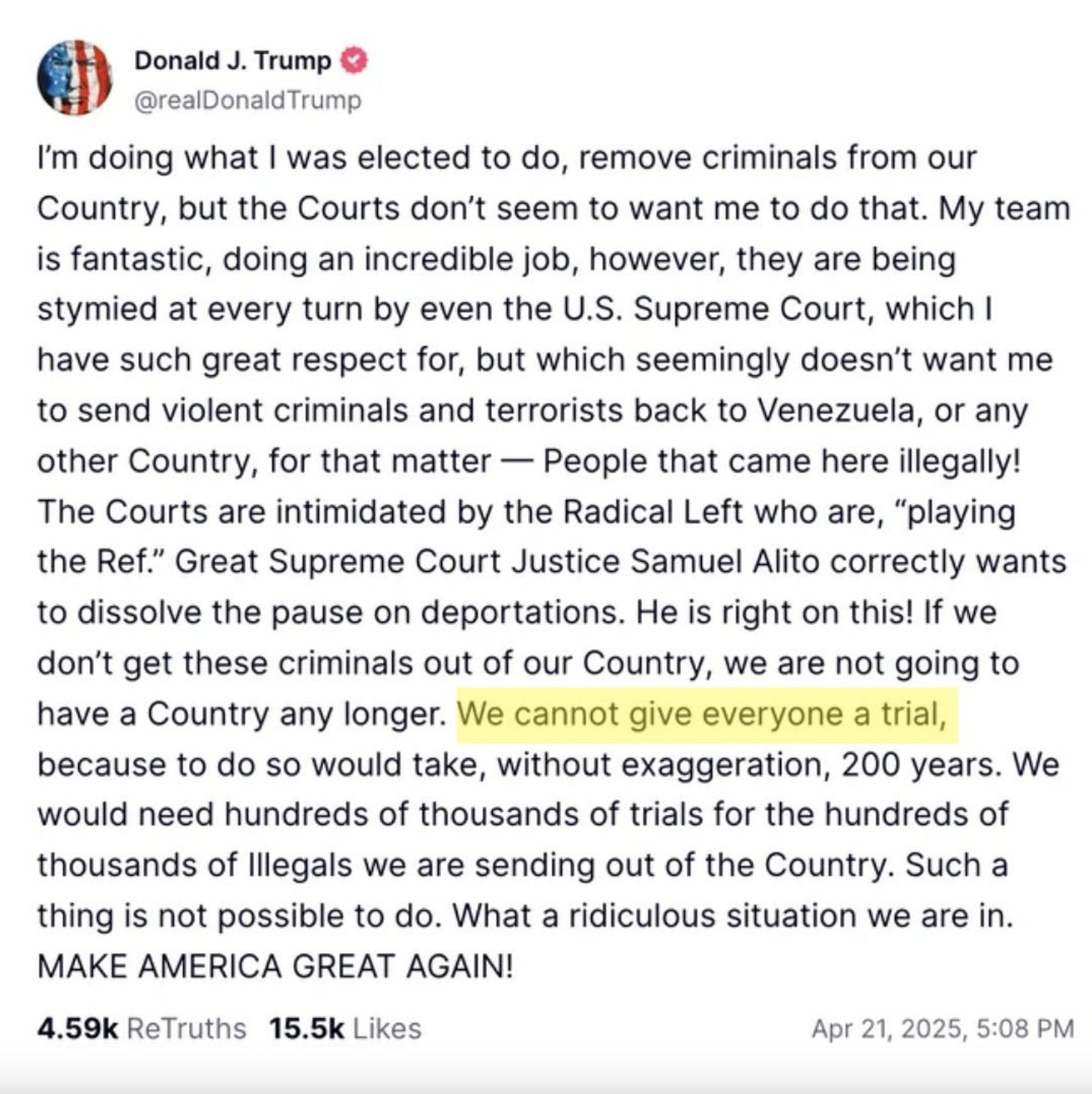

Which is why his observations about the cyclical patterns of history - and how they influence creativity and civilisation - are a tad concerning in the context of the period we’re currently living through; in which technology, cultural anxiety, and political rage are combining in ways that would’ve had Nietzsche nodding grimly from the sidelines.

Case in point: the philosopher’s ongoing series of conversations with his pal Jacob Burckhardt, during which they reasoned that true creative energy often emerges out of societal extremes - especially violence and upheaval.

This, the pair decided, meant that “extreme barbarity is no cultural hiccup occurring only when a civilisation is sliding into decadence; rather, it is a necessary part of the fabric of creativity.”

In the end, they bleakly concluded, this inevitably leads to “demagogues armed with all the potentially terrible weapons provided by industrialisation, science and technology” wreaking barbarous havoc on society.

Remind you of anybody?

3. Even geniuses have to battle health issues

“Does the mind rule the body?/Or does the body rule the mind?/I dunno” - The Smiths

Nietzsche’s creative doggedness in the face of a truly grim list of health issues is almost comically bloody-minded.

Take the summer of 1872. His eyesight had deteriorated to the point where “light was agonising.” He spent his days in a darkened room, venturing out only when cloaked in a sunshade, thick-lensed green-tinted spectacles, and a beak-like visor jutting out over his forehead.

Things got worse. A prescription of “eyedrops of deadly nightshade” - yep - doubled the size of his pupils, turned the world into a “dancing blur,” and gave him such a grotesque appearance that even his closest friends recoiled.

For someone whose life revolved around reading and writing, this could have been a death blow. But with the help of his sister Elisabeth, who managed the domestic side of things, and his friend Carl von Gersdorff, who read aloud to him and helped organise his source material, Nietzsche carried on. More than that, he somehow turned this wretched episode to his advantage.

As Prideaux reports, von Gersdorff believed this laborious new method actually sharpened Nietzsche’s thinking: “both his material selection and his delivery were improved… which left Nietzsche speaking more clearly and eloquently, and with more concentration.”

Nietzsche, unsurprisingly, took it even further - casting the whole ordeal as a personal breakthrough:

“The illness gave me the right to change all my habits completely; it permitted, it required me to forget… my eyes alone put an end to my bookworm behaviour; I was redeemed from ‘the book’…. The greatest blessing I ever conferred upon myself.”

One to remember the next time the man-flu kicks in.

4. All creative people are fragile snowflakes

One of the joys of reading this book is the frequent and often hilarious reminder that even titans like Nietzsche and Wagner were basically stressed, petty creative egomaniacs - endlessly fretting over why their friends hadn’t fed back on their latest work, how they were going to fund their next project, why nobody would review their book, and so on.

Consider Nietzsche’s ongoing battle with his own planet-sized creative ego. On the one hand, he’s the epitome of the lone, questing intellectual - railing against newspapers as a destructive new technology destined to obliterate attention spans and distract the masses from serious thought.

On the other, he’s absolutely desperate for his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, to be reviewed. Anywhere. By anyone. When it finally is, he celebrates by buying fifty copies of the review.

No less relatable are the constant stresses about money and budgets.

Even Wagner - who’d been gifted one of the grandest houses in Switzerland by King Ludwig II, and given free rein to redesign the entire town of Bayreuth in his image (all at someone else’s expense) for his planned festival celebrating his own work (it still takes place every year) - never stopped worrying about how he was going to pay for his next project.

Above all, like every artistic person since the dawn of time, Nietzsche was quietly terrified that his work was rubbish.

As a result, he constantly sought validation from his peers — like the time he unwisely tried to win Wagner’s approval for his own amateurish musical compositions.

That Nietzsche was a brilliant musical improviser was unquestioned; so much so that one spontaneous performance apparently moved Cosima Wagner to tears.

Unfortunately, his famous pals were less enamoured with his ability as a composer, and when he wrote an original piece called Manfred Meditation as a Christmas present for Cosima, trouble ensued.

Using a devastating passive-aggressive tactic familiar to anybody wondering why their close friends haven’t liked or shared their latest work on Instagram or Facebook, Cosima and Richard Wagner disliked it so much they simply pretended it had never happened: even ignoring Nietzsche’s plaintive, ill-advised letters on the subject, in what has to be one of history’s more brutal ghostings.

Unfortunately for Nietzsche, his old friend Hans von Bülow had no such scruples, sending him a devastatingly frank critique, in which he described Manfred Meditation as:

“...the most extreme in fantastical extravagance, the most unedifying and least uplifting, the most anti-musical thing that I have come across in a long time in the way of notes put down on paper... More than once I had to ask myself: is this all some awful joke? Did you perhaps intend a parody of the so-called Music of the Future? Is it with conscious intent that you express an uninterrupted scorn for all the rules of tonal connection, from the highest syntax to the usually accepted orthography?”

As Sue Prideaux explains, the impact was devastating. Nietzsche didn’t leave the house for three months, and it would be decades before he dared share his music with anyone outside his immediate family.

5. If in doubt, self-publish

Considering how little he is understood or even read these days, Nietzsche’s influence has always been outsized. Perhaps it’s because he embodies one of the most romantic and poignant creative tropes of all: the questing artist who dies in obscurity, only for his work to be belatedly discovered and celebrated after death.

Success - of a kind - came early, thanks to the moderate reception of The Birth of Tragedy, which briefly caused a stir among Europe’s intellectual class.

From there, commercially if not creatively, it was downhill all the way. Some of the funniest (and most recognisable) relationships in I Am Dynamite! are between Nietzsche and his long-suffering publishers and editors - endlessly tearing their collective hair out as the writer disappears down ever-more quixotic paths, submitting commercially suicidal (and, by the end, illegible) manuscripts; torpedoing his already tiny audience with every release.

Not that Old Dynamite himself cared. In fact, the less well-received his work was, the more he doubled down.

When his publisher Ernst Schmeitzner flat out refused to publish the fourth volume of his Thus Spoke Zarathustra series, Nietzsche cashed in part of his University of Basel pension and printed a meagre forty copies himself, distributing them to a small coterie of friends and colleagues - hardly any of whom acknowledged its existence.

By 1886, Nietzsche was eking out a bleak, peripatetic existence, living off that same meagre pension, and moving between small hotels in Turin, Sils-Maria, Florence, and Nice,

And yet, still, the revolutionary work continued, as Prideaux describes:

“Seen from the outside, Nietzsche's life during 1886 and 1887 looks quiet and harmless, but it was during this time that, with all the fury of the neglected prophet, he was examining the foundations of our moral and intellectual traditions and taking a hammer to them in the books of his mature philosophy.”

The result was his magnum opus, Beyond Good and Evil, which, once again, he decided to self-publish:

“As no publisher had the slightest interest in publishing his work, he would publish it himself. He would have it printed privately at his own expense in an edition of six hundred copies. If he sold three hundred, he would get his money back. Surely that was not impossible?”

In the end, it sold a mere 114.

Months later, Nietzsche would be certified insane. He spent the rest of his short life being shunted around various insane asylums, completely unaware that his work and ideas had finally achieved the global renown he always craved: let alone that he would eventually be considered one of the most influential figures in twentieth century culture, cited by everybody from Stanley Kubrick (see below) to Don King (true story).

And maybe that’s the thing to remember. Despite the illnesses, the rejection, the feuds, the mortifying reviews of his musical side hustles, and the shockingly poor sales figures - Nietzsche kept at it until the very end.

Something to keep in mind the next time you’re staring down a blinking cursor, or a half-finished side project, and wondering what on earth the point is.