Insights: Chris Nelson - The Big Sea

Writer and producer Chris Nelson on what he's learned while bringing The Big Sea to the big screen.

This week’s Insight’s post is free-to-read for all. I wanted to give free subscribers a look at what Insights subscribers are getting every week as part of their subscriptions.

To find out more about Insights, what extras paid subscribers get, and how to make best use of your paid subscription, read my guide:

If you’ve been listening to my podcast Looking Sideways at all closely recently, you’ll have heard me talk about how increasingly fascinated I am by a phenomenon I have been calling ‘the purpose gap’.

What do I mean by this? I mean the gap between the purposeful rhetoric of people and brands - black squares on Instagram, pride flags on contest jerseys, and so on - and the contrasting reality of their day-to-day actions.

To a degree, of course, everybody is guilty of this act of consistent cognitive dissonance.

It’s why the challenge of ‘how to reconcile being principled while also being a participant in such a rapacious, growth-based system such as capitalism’ is such a key theme of The Announcement, my forthcoming documentary about Patagonia’s decision to give away the company and make ‘earth’ their only shareholder.

“Your politics are not what you tell yourself you believe. Your politics are expressed in the choices that you make, the way you treat other people, and the actions you perform. It is here that hypocrisy and vanity fall away, as the reality of your politics is revealed in the countless decisions that you make every day. Who you work for, whether you volunteer for charity work, if you become a landlord, whether you eat meat, the extent to which you pursue money and consumer goods - these are the types of decisions in which our true politics are expressed” - John Higgs

Examples of this are everywhere. It’s one reason why people are so up in arms about the WSL decision to hold an event on the 2025 Tour in Abu Dhabi, for example.

It’s why I’m personally so choosy about what opinions I espouse, what events I attend, and what causes I lend my support to.

And it’s one of the reasons I have been so forthright in my support of forthcoming documentary The Big Sea since I saw the original cut of the film two years ago.

For one thing, as an independent practitioner of journalism who isn’t beholden to the whims of advertisers (imagine that!), I recognised straight away that this is the biggest story in town.

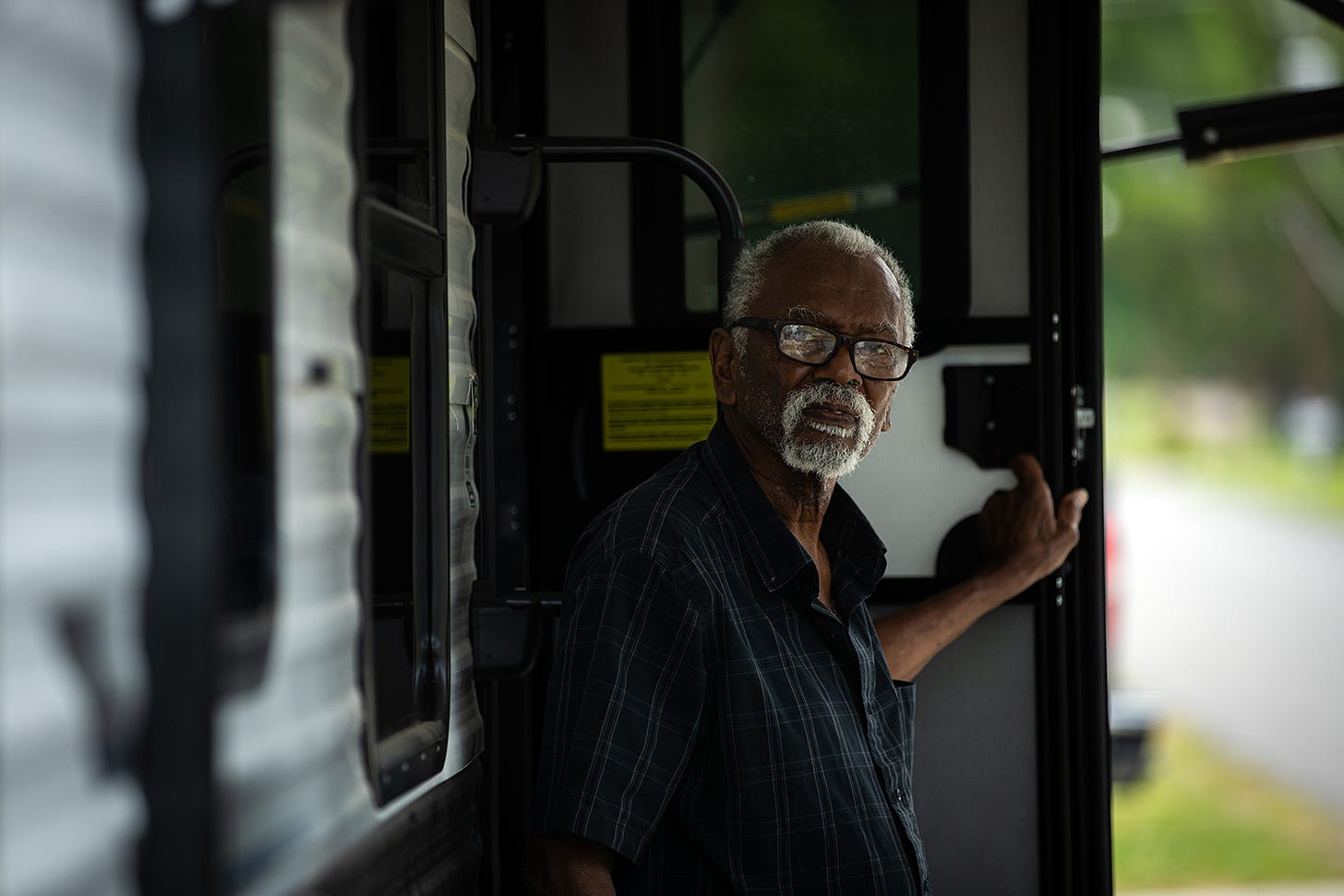

In a sane world, where the purpose gap wasn’t so commercially ingrained, the shocking narrative that drives The Big Sea (the carcinogenic impact of neoprene production; how it predominantly affects Black and low-income communities in Louisiana, which now have a cancer risk 50x higher than the US average; and how the surf industry appears to have been almost wilfully unaware of this connection) would have elicited outrage and immediate action.

Especially when, in Yulex and other plant-based materials, there has long been a readily available solution at hand.

But there’s another reason why I have been so vocally behind this documentary. And that’s because the Big Sea project itself is a very rare example in our industry of purpose being followed through with action, integrity and principled consistency.

Film-makers Demi Taylor, Lewis Arnold and Chris Nelson have been dogged and principled in their pursuit of this story, often in the face of obfuscation and self-interested indifference.

This is not a project that is concerned with how it is going to land in particular markets, or whether it’s going to upset key players in the surf industry - even though it undoubtedly has, and with evident consequences for the film-makers themselves.

The resulting piece of work is a powerful, shocking and beautifully-made film that Surfers Against Sewage co-founder Chris Hines MBE describes as “the most focussed 70 minutes of environmental and social campaigning by surfers ever.”

“So powerful. So well told. So poetic. The engine-message-activism that drives the film is so important, but it's also very beautiful, with stellar, arresting cinematography.” - Jamie Brisick

What’s why, in this Insights blog, exclusively for my paid subscriber community, I asked Big Sea writer Chris Nelson to share the lessons he’s learned in the five years the team have spent working on this project.

Over to Chris…

1. There is the surf industry – and then there’s surfing

Surfing is an incredible thing. It is filled with joy, passion, stoke. Yes, there are days when it hurts. Days of frustration. But it is highly rewarding and highly addictive. There is a certain common bond we all share. I once travelled to Hokkaido on a surf trip. I got off the final flight into Sapporo and walked out into the snow as the last passengers ebbed away. I was the only figure at the now closing airport, waiting for a person I’d never met, never spoken to. But, he was a surfer. We’d emailed. He said he’d be there and I never doubted it. A few minutes later his mini-van pulled up and we hugged. This is surfing. We are an extended family.

Then there’s the surf industry, which is ultimately just that. An industry. There’s this inbuilt assumption – a benefit of the doubt implied with simply being a surfing brand – that it is somehow is more invested in the environment.

But that’s just not the case anymore. The surfing industry is a $10 billion global marketplace, many of the brands are venture capitalist-owned and motivated primarily by the single bottom line – profit - with little thought for the other two elements you often see referenced on the same surf websites: planet, purpose. Can we assume that a surf brand has a deeper connection to the environment than say… a tennis brand?

The surf industry is also overwhelmingly overseen by white, middle-class males. It’s a boy’s club. Counterparts at many brands know each other. They hang out at contests and trade shows, go for beers together, maybe surf together. They’re mates. They’ve come up through the industry together. The same is true of many in the surf media.

But what happens when someone in the club suspects something is wrong? Who is going to rock the boat? Who is going to ask the awkward questions?

Sometimes silence springs from a collective directive to suppress. But more often than not, it comes from self-censorship. We’ve seen this in other industries – like entertainment and #MeToo. A scandal erupts and everyone says, ‘How come we didn’t know?’

Except it turns out that, of course, people did know. They just didn’t want to be the first to say it.

Despite the number of surf brands using Neoprene, despite the number of product managers whose job it is to oversee materials and supply chains, there has been an overwhelming reluctance to engage in the conversation exploring the links between chloroprene rubber, surfing, wetsuits and Cancer Alley. The collective silence from the industry has been deafening.

Surfers, on the other hand, are keen to understand what’s in their wetsuits, how are they made, where they come from, and the impact they have. That’s what we’ve tried to show in our film.

2. Could Limestone Neoprene be surfing’s Dieselgate?

This is a question that I’ve been mulling over for a while now. In the wider industrial complex, if you bring a product to market with a sustainable label, the first thing people ask is ‘show us the proof’.

Yet so-called Limestone Neoprene has been marketed to consumers as ‘environmental’, ‘sustainable’ and ‘green’ for over a decade, despite the case for this being tenuous as best.

Scientists we spoke to during the making of The Big Sea confirmed that Limestone Neoprene has a carbon footprint that massively exceeds that of petrochemical Neoprene, which suggests a particularly egregious case of greenwashing. Consumers bought (and paid a premium for) Limestone Neoprene on the understanding that they were purchasing the green option. And yet the reality is that this material is made from an intensively quarried rock, which is melted in a huge furnace before being fed into an energy intensive chemical plant that eventually produces… yes, toxic chloroprene rubber.

So why are brands so wedded to this substance? And why do they continue to market it as sustainable, despite all evidence to the contrary? Could the answer be…

3. A secret mountain of post-Covid inventory?

A number of off-the-record briefings from brands, either to offer support or excuses, would seem to suggest as much. According to these accounts, one of the justifications levied by a number of brand insiders as to why they aren’t moving more swiftly to natural rubber is the so called ‘Neoprene Mountain’.

The story goes that during the Covid restrictions many lapsed surfers returned to the line-up. Boards were dug out of garages. New wetsuits were purchased, causing a surge in sales. Brands eager to cash in ordered more stock.

Then in March 2021, the Suez Canal was blocked for six days by the Ever Given, a giant container ship that wedged itself in this vital trade artery, causing a global $10 billion supply chain traffic jam.

Surf shops ran dry. There was a scramble for stock. And when the Ever Given was finally freed, there was an unintended consequence: all this new stock arriving at the same time, just as the world returned to work and the surge in demand dropped off.

“I’ve been inside the main warehouse at (REDACTED),” one industry insider told me. “It’s absolutely crammed full of unsold wetsuits.”

Now THAT, I imagine, could be a pretty powerful headwind to change.

4. Inertia is a powerful thing

Surfing is dynamic and fluid; ever-changing, fluctuating; shifting with the tides, the days and the seasons.

Yet the surf industry is a giant, unwieldy behemoth. Take the case of Gordon ‘Grubby’ Clark, who dominated the global surf blank industry until he abruptly shuttered the business in 2005.

At the time it was seen as a chance to break away from the toxic and environmentally unsustainable technology that had dominated surfboard manufacturing since just after WW2. New brands did emerge, offering cutting edge ideas for surfboard composites and innovative materials – and yet today, most surfers are still riding the same type of boards, manufactured in the same style. Toxic and unsustainable. New blank producers popped up and filled the gap in the market, drowning out innovation. Whatever the issue, whatever the chance opportunity to show visible leadership, the industry seems to quickly settle into the status quo.

The difference when it comes to wetsuits, and the issues we raise in The Big Sea, is that the solution is immediately at hand.

There is already a readily available alternative to petrochemical or Limestone derived chloroprene rubber: natural rubber – from a tree.

What could be better? It is cheaper than chloroprene. It’s sustainable. The trees it comes from pull CO2 from the atmosphere, rather than adding to it. And, crucially, it’s accepted by the industry to perform as well as, if not better, than Neoprene.

If brands shift we can have cheaper, better, environmentally-friendly wetsuits as standard within a few years. And change is happening. From giants like performance wetsuit brand Xcel committing to be Neoprene-free by 2026; to small, agile brands like Wallien for whom this film was a catalyst to move to Yulex – there is a transition taking place away from toxic Neoprene to natural rubber.

5. I still believe that surfing has the power to affect change.

The Big Sea tells a simple yet complex story.

On one level, is the time-worn tale of Denka, a powerful multinational, discharging toxins into the environment and devastating a disenfranchised local community.

On another, it’s a human story of two seemingly unrelated communities bound together by one issue.

And it is also a many-layered narrative that encompasses historic repression, slave plantations, environmental racism, the opacity of global supply chains, and the blinkered nature of a culture that considers itself a bastion of environmentalism.

With any story I tell, I feel pressure to do it justice – but with this one there are real ramifications. This is literally a life and death tale, and it has been going on for years. The people of St John have told their stories of loss and suffering to countless journalists from many outlets across the globe, but change hasn’t come.

They deserve better. And I believe the surf community can be the ones to lead the change.

That begins with a simple decision - using our purchasing power to make a difference, stop buying Neoprene, and stop supporting the brands that support Denka, and put money its pockets.

In addition, you can lobby your favourite surf company. or wetsuit manufacturer, and ask the, why they are still wedded to a toxic chemical with links to Cancer Alley – when there is a natural alternative that is as good, if not better.

The river parishes along the banks of the Mississippi have a dark past. The soil is steeped in suffering and injustice, and the air is now heavy with pollution.

But there is still a chance that the surfing can work with the communities in Louisiana to usher in a brighter future.

I am hosting two showings of The Big Sea in November, at the London Surf Film Festival, and the Kendal Mountain Festival. Get tickets via the links

You can find out more about The Big Sea and the facts behind surfing’s links to Cancer Alley here.

Let me know what you thought of this one using the big shiny button below:

Thanks for making this free to read Matt. I backed the fundraiser, so pleased to hear it's turned out well. I will subscribe soon!!

Hey Matt&Chris. Thanks for bringing this topic to our attention and keeping us updated! I am really looking forward to see the movie and the response of the industry. Your first episode on Type Two inspired me to write my thesis about chloroprene production. It is still very strange to see the number of eco-friendly claims about limestone without any quantitative proof, or at best, rather bold assumptions.

A common argument for limestone's environmental benefits is that one specific limestone rubber production site sources 40% of its electricity from hydropower. However, because of the substantial electricity demand, my research showed that this does not significantly reduce limestone's environmental footprint enough to make it a cleaner alternative to it's synthetic brother made from butadiene, let alone natural rubber.

If you're interested in checking the results, you can find my research over here:

https://repository.tudelft.nl/record/uuid:c5a29965-cc60-4cf0-8b2f-bd0651e0d1e5

Keep it up!